What They Saw in Armenia and Armenians

Posted on September. 10. 2021

by Vitali Ianko, former professor at Brown University

They, otars (in Armenian) or foreigners, were explorers and scientists, religious and military figures, merchants and missioners, and idle travelers who left accounts describing their encounter with Armenian land and people. In my book collection, side by side with well-known titles, are books written by now totally forgotten authors. Nevertheless, some of their remarks and comments are so eloquent and poignant that they undoubtedly deserve to be brought up and remembered.

Read this one: “… the old culture, one supposes, had vanished as surely as all the other civilizations that are gone; leaving what? Only an impress on human character, and on the imagination of those who knew it. That is the contribution made by the culture of the Hayq. It carries, much as Ararat carries its snow, something of the majesty of simple human being, unobscured by the smoke-clouds of the western world.” Theselines are from the small unassuming book, An Island in Time. Charted by Sirov of Kanakir, (1924), written by Henry Chester Tracy (1876-1958), an American zoologist. The main character of the book says: “I do not pose as spokesman for the Hayq, whom the Arabians called Armen; but I shall be supported by the genius of that race when I say this: it has never been our wont to beat our heads against the wall and bewail the immobility of our fate. Denuded of all that we valued in vineyards and homes, we have been allowed, by our destiny, to hold the kingdom of our souls. We shall not call ourselves pitying names. Richer people have lost that kingdom before now.” Sirov’s words about some rulers of Armenia sound like they were said today – “They were figure-heads, inflated with power; pompous effigies, inspired from behind. At best they understood intrigue and the taking of bribes.”

A group unknown authors hiding under odd penname Oriental Widow wrote the book, Light Thrown on a Hideous Empire, (1897), containing the following description: “Swallows traversing the thousand miles of mountains and valleys which divide the Black Sea from Tigris find, in the course of twelve hours, spring in Trebizonde, winter in Erzerum, and summer in Mosul … Such, then, is Armenia, whose centre is a vast elevated plateau, girdled in by mountains of imposing grandeur, and whose crowing glory is Ararat, towering far above into almost paradisiacal beauty, further heightened by an immortal and fadeless diadem of eternal snow circling round the giant’s brow in that sublime atmosphere beyond the clouds, fit emblems of life’s transient joy and sorrow. Here in summer the heat is often so great as to melt the lead on the cupolas, whilst the semiarcticwinter is little inferior in its rigours to that of Lapland, nearly 3,000 miles further north. It will be thus seen to what an extent the Armenian people have been influenced by the physical considerations of their native land, to which, at any rate, they owe their energy, tenacity of purpose, and determination to exist as a nation. Come what may, and in spite of all barriers, whether political or religious, blotted out for more than five centuries from the list of independent nations; divided at the present moment into three portions, shared respectively by Russia, Turkey, and Persia, subject to vile persecutions by the two latter; and weakened in cohesion by its wealthiest population, i. e., merchants and traders, being scattered throughout the Levant and remoter Eastern provinces; it has more the less preserved it vitality, patriotism, and undying hope, unchanged across the centuries, that the Fatherland not only may, but will, be restored on the fall of the Turkish Empire.”

Missionaries, who by virtue of their work assignments stayed in the Near East for long years, knew better than anybody else about character, morals, and abilities of Armenians. “Among all those who dwell in Western Asia they (the Armenians) stand first, with a capacity for intellectual and moral progress, as well as with a natural tenacity of will and purpose beyond that of all their neighbors – not merely of Turks, Tartars, Kurds, and Persians, but also of Russians. They are a strong race, not only with vigorous nerves and sinews, physically active and energetic, but also of conspicuous brain power.” (Near East Relief. Hand Book, 1920). It did not matter where Armenians lived; they everywhere excelled and thrived. “The Armenians are in general fine men, robust and with intelligent physiognomy. Their complexion is vivid, their beard flaxen or chestnut-coloured and their eyes black or blue. They are unsurpassed in business, very clever, polite and agreeable as companions. They are well informed for the most part, knowing many languages, and occupying good positions in the different administrative departments of the state and in the great financial establishments.” (Gaston Souhesmes. Guide to Constantinople and Its Environs, 1893). Savage-Landor (1865-1924), an English painter, explorer, and writer noted upon visiting in 1901 the town of Julfa with its predominant Armenian population: “The Armenian man – the true type of Levantine – has great business capacities, wonderful facility for picking up languages, and pervasive flow of words ever at his command. Skeptical, ironical and humorous – with a bright, amusing manner alike in times of plenty or distress – a born philosopher, but uninspiring of confidence – with religious notions adaptable to business prospects, – good-hearted, given to occasional orgies, – such is the Persian-Armenian of to-day.” (Across Coveted Lands …,1902).

Many marveled on Armenians’ ability for “picking up languages.” Here is just one example, but a vivid one, observed in Constantinople: “In the shop near the gateway many languages are spoken by the Armenian proprietor. He explains in fluent English the virtues of the black and yellow amber cigarette holders, while with the accent of a Persian, he begs a Frenchman to be seated, and Italian sailor is told the price of a little box in his own language; the assistant receives his orders in Armenian; a passer-by is signaled in Turkish; and all this takes place within the space of a few minutes and without the slightest effort.” (Louise McIlroy. From a Balcony on the Bosphorus,1924). What concerns “occasional orgies,” those most likely were Westerners’ misperception of good-hearted gestures of traditional Armenian hospitality. And here too one well-pictured example is enough: “While in Shiraz, I had the good fortune to be invited to an Armenian banquet. It was a magnificent entertainment. We sat down, thirty in number, on either side of a long table-cloth, spread on the floor, and covered with various kinds of pilau and other dishes, including a lamb roasted whole. Beer and Shiraz wine flowed freely. The dinner was followed by drinking of healths. A dignitary of the Armenian church, second in rank (I believe) to the bishop, who had come from Isfahan to grace the occasion, was the principal speech-maker. He preferred cherry brandy of terrific strength, and with decanter affectionately grasped and held in his ample lap, among the folds of his black cassock, while the other hand held the glass ready for the generous liquor, he delivered several speeches in Armenian, with evident eloquence, and not without dignity and grace. The custom is that the person whose health is proposed should acknowledge the honour in song while the company are drinking, and afterwards return thanks in prose. Our ecclesiastical dignitary kept up a deep running bass that would have done credit to the drones of a couple of bagpipes. The whole thing was excellent fun, and had that heartiness and kindness about it …” (Edward Stack. Six Months in Persia, 1882).

Otar visitors also were not short of words while stinting their praise of Armenian women’s beauty. While traveling through Turkey, Countess Mathilde Pauline Nostitz (1801-1881) visited the town of Aintab where she mingled with Armenian women. “They are unveiled indoors, but do not allow themselves to be seen by any strange man … It is the more to be regretted, as the screen often conceals a galaxy of beauties. At Aintab I really saw the much lauded oriental beauties whom I hitherto looked for in vain … As I have said before, I was greatly surprised, among the twenty women whom I saw that morning, to see at least eight classic beauties. The regular oval of the face, the finely formed nose, the large dark eyes shaded by long thick eyelashes, the brilliant complexion of these southerners form an incomparable whole.” (Travels of Doctor and Madame Helfer in Syria…and Other Lands, 1878). Another admirer noted that “much has been written and told of the beauty of Armenian women,” in which he readily concurred and spent almost two pages painting a picture of a young Armenian lady lauding her “exquisite forms, capricious vivacity, coquettish gracefulness, brilliant placidity, and luminous clearness.” (Randal Roberts.Asia Minor and the Caucasus, 1877). In descriptions of Armenian men physical characteristics of strength and endurance were detailed. The famous Constantinople hammals(porters) were looked upon by visitors with true amazement: “These men, who form one of the distinctive features of the city, are usually Armenians and come from the mountain regions of Van, bringing with them the superb vigor and strength of the mountaineer. Broad-chested, long-bodied, clean-limbed, with muscles standing out like whipcord, it is popularly said that they can carry four times as much as a man can lift on his shoulders … Their diet is simple in the extreme, consisting of bread, black olives, cucumbers and cheese – cheese always – cheese with watermelon and cheese with grape – but cheese. It is among these hammals that the descendants of the ancient Armenian kings may often be traced. They possess the Armenian characteristic of natural humor that often finds expression.”(James Boyd. Travels in Many Lands …, 1899).

Being by themselves for centuries harshly persecuted people, Armenians always demonstrated genuine understanding of and sincere compassion to the sufferings of the others. They all, from intellectual elite to working class, were sensitive to the pain of the oppressed. Vasily Grossman, a Soviet-Jewish writer (1905-1964), spent two months in Armenia observing customs and traditions of her people and interacting not only with Armenian writers but also with common people. Upon his return to Moscow he published book about his journey titled, Wish You Well, as a paraphrase of the Armenian greeting, Barev Dzes. Only one passage was deleted from the publication by Soviet censor: “I kneel to Armenian peasants in the mountain village who during wedding gaiety publicly talked about sufferings ofJewish people in time of Hitler’s savagery, about death camps in which German fascists slaughtered Jewish women and children. I kneel to all of them, who solemnly, sorrowfully, in silence listened those speeches … To the end of my life I will remember Armenian peasants’ speeches.”

There had been, of course, biased opinions, scattered here and there in travel accounts, telling to ill-informed readers that “timid, unwarlike” Armenians were good only for making money but not for fighting. The real facts evidenced that Armenian man, be he a rich city-dweller or poor farmer, could demonstrated splendid fighting skills defending his family, his village, his country. During the 1905 Armenian pogroms in Baku, “the Armenian Adamoff, a millionaire who was also a crack shot, was cut off in his house by a mob of yelling Tartars. With his rifle, bandaged and helped by his young son, he defended himself for days, picking off each daring Tartar who tried to rush the house. In the end they got in and massacred everyone in it, forty in all. When they counted the Tartar corpses, it was found Adamoff had shot just forty. It was not so easy to find out who had gained.” (Glyn Roberts. The Most Powerful Man in the World, 1938). When Eleazar Demodoff, a scion of one of the richest families in Russia, hunted for ibex or wild mountain goat in Armenia (Alagueuz Mountains), he met a Russian officer who did not think at all highly about fighting capabilities of the Armenians, finding the Kurds as much more formidable opponents. However, Demidoff’s hunting guide, a middle-aged Armenian named Kaloust, served as a total disproof of the officer’s gossip. Kaloust “was an excellent hunter with extensive and peculiar experience in stalking, having not always confined himself to the lower animals … two years ago, while hunting on the Persian side, when his comrade was assailed by three brigands, he came to the rescue, and, getting two of the enemy in a line, shot them both dead with one bullet. Then he and his comrade cut the remaining man’s throat, so as to avoid any unpleasant recriminations.” (Hunting Trips in the Caucasus, 1898). Another traveler, the correspondent for The Times, met some truly remarkable characters among Armenian freedom-fighters such as, Rustum Keri, a bomb-maker, who recited poems by Byron and Scott in Armenian, Russian, and French, or Zoarabian, a family man and “a tiger to fight.” Most famous was Yeprem – “he had the great head and lustrous eyes of a poet, and a low-toned, musical voice, a gentle as a woman’s … the Russian government had sent him to Siberia, whence he had escaped to Persian soil, and at Resht thrown in his lot with constitutional movement. He fought innumerable fights with mere handfuls of men, always against tremendous numerical odds, and was never once defeated … he once told me that he knew that he would never die in his bed; and his words came true at Hamadan, when he and Sohrab Khan fell together.” (Arthur Moore. The Orient Express, 1914).

The following lengthy passage deserves of its citing because of succinct characterization of fighting capabilities of Armenians and their two neighbors and also because it was found in an obscure book, undeservedly consigned to oblivion. It’s author, a British journalist, spent a considerable time traveling in region in 1919-20 and meeting with many military and political figures. “It was commonly stated in Batum that the Georgian Government at that time had agreement with the Tartars of Baku against Armenians, and with Armenians against the Tartars, with us against the Turks, and with Turks against us, with Bolshevists against General Denikin, and with other people against the Bolshevists, with the Germany against Allies, and with the latter against the Germans … I cannot vouch for the accuracy of the whole of this accusation, but I do certify that it sums up the pleasing spirit of opportunism that was displayed by the Georgian leaders … The Tartars of Baku, whom I visited later, were led by men of much the same stamp. In both cases the outcome of their policies was the same. The moment that the Bolshevists, having defeated Denikin, decided to enter their respective territories, the local Governments disappeared with much clatter and no real resistance. Their respective republics collapsed like card houses and the Bolshevists walked in unopposed … The only people for whom I acquired respect were the Armenians. When I went to Armenia I was astonished to find that, with all their many faults, the Armenians stood head and shoulders above their neighbors not only in intelligence but also in courage. Ever since the day when I first visited the trenches in which miserably small and ill-equipped Armenian force was resisting a far more numerous and better armed army of Kurds and Turks, I have had an admiration for this people, so basely betrayed by allies with whom, alone of all the people of the Caucasus, they have always kept faith, and who have requited them with neglect, forgetfulness, broken pledges – how many of them! – and even definite hostility. We could so easily have kept our promises to the Armenians, with some advantage and little cost to ourselves; but we have not done so.” (Eric Bechhover. A Wanderer’s Log, 1922).

And indeed, they all – the French in Cilicia, the British in Baku, and the Russians in the Caucasus, and even Americans with Wilson’s paper map of Independent Armenia – all so-called Allies and Great Powers betrayed and sold Armenians on every corner. After Turkey’s defeat in the World War I, they all profited, but Armenians had gotten nothing. “They had fought under every Allied flag. They had fought so hard that of 900 Armenians in French Foreign Legion only 50 survived. When Russia collapsed, an Armenian army took over the Caucasian front and held it for five months. Ludendorf has been quoted as saying that in this campaign the Armenians won the war by cutting off Caspian oil from the Germans. But as usual, behind the vapor of pious promises, the Allies had been sweating over their secret treaties. They drew up not less than six plans for carving Turkey, and dividing the slices … In none of these six carvings did Armenia appear as a slice to herself … it has always been the contention of the Armenians that the French had promised them in Cilicia, not only protection but autonomy; and this as an express reward for military service. But when these Armenians asked for their reward on the spot where they had earned it, they were invited to go further north, and General Gouraud said to them, ‘you don’t expect us to make an Armenia in every corner of the world, do you?’” (Herbert Fisher. Alias Uncle Shylock, a Tragic-Comedy of the Two Dromios, Fear,Avarice, 1927). And each new betrayal had been met by Armenian political leaders with shock and dismay as if it happened for the very first time. Such things happened hundred years ago and is happening now! Robert Dunn (1877-1955), an American journalist and intelligence officer served under Admiral Mark Bristol, who was defending the US interests in the Near East after the Armistice. At that time, great powers were excited by carving the still warm corpse of the Ottoman Empire, but they already knew they were not going to fight for Armenia, a mandate over Independent Armenia was a fiction. Dunn was with his master in a Batum hotel during his important meeting with the President of Armenia: “Upstairs in the ballroom, Admiral Bristol sat with the president of the new Armenia, a man named Khatissian. His excellency, in frock coat and rimless pince-nez, was hefty, handsome, with black moustache brosse over an imperial. Mark’s French was shaky so he sent down to me to interpret their talk. ‘Tell him,’ admiral said, ‘that any small weak country in these parts must in time be taken over by its strongest neighbor. In his case, Russia.’ “Non, non!’ said Khatissian, shocked. ‘He must see that in a couple of years his Armenian republic will be under Moscow, whether it’s Red or White by then. Say I’m sorry, but that’s truth.’ This angered the president. Warned that Azerbaidzhan and Georgia faced the same fate, he couldn’t take it. We left him silent and sulky.” (World Alive: A personal story, 1956).

It was Red Russia, and from the very beginning it showed that it wouldn’t care much about interests of Armenians. On March 3, 1918, in Brest-Litovsk, Russian Bolshevicks signed a treaty with Germany in which Article IV stipulated the evacuation of Ardahan, Kars and Batum by Russian troops. A separate treaty of the same date provided that “the Russian Republic undertakes to demobilize and dissolve the Armenian bands, whether of Russian or Turkish nationality now in Russian and Ottoman-occupied provinces and entirely disband them.” Those treaties rendered Armenians defenseless against the continued invasion of Turkish troops and wide-spread massacres in Armenia and Karabagh. (Alfred Dennis. The Foreign Policies of Soviet Russia, 1924). In Mosul, wrote Victor Shklovsky, then an Assistant Commissar for Russian Expeditionary Corps, Russianssigned “shameful conditions of armistice” with Germans, forcing the removal of their troops still remaining in Persia. Notorious Khalil Bey, who “had gotten a glory burying in the dirt 400 Armenian newborns while leaving Erzerum to advancing Russians,” was a representative for Turkey in Mosul. Turks were delirious with happiness, kissed Russian parliamentarians, and danced on the streets. Armenian women, who were deported to Mosul from Armenia, were catching horses’ tails of the leaving Russians and begging Cossacks to save them. “Russians were riding in silence …” (A Sentimental Journey: Memoirs 1917-1922). Doesn’t all this look painfully familiar to people now living in Artsakh?

An otar may be astonished by inept diplomatic efforts of Armenian state, by the trustfulness, if not naivety, exhibited by its leaders who routinely signed agreements which looked good only on the paper and joined unions with other states whose declarations of mutual military and trade assistance did not cost more than price of stamped papers on which their deceptions were printed. However, one glance on the map of the Caucasus would explain that Armenians, squeezed from both sides by their blood-thirsty enemies, had no other choice as to look north for protection. Unfortunately for Armenians, their only Christian neighbor historically showed total insolvency as an ally, often taking up a traitorous stance or, at least, trying to profit from Armenians’ misfortunes. When after the 1917 revolution Russian soldiers abandoned the front positions, Armenia and Georgia were left alone to deal with the Turks. “A verbal agreement has been reached between Armenians and Georgians according to which the former were to defend Erzerum and the latter the Trebizond front. When the Turks advanced, however, the Georgians did not show up at Trebizond and the Armenians were left alone to fight the Turks. They offered heroic resistance, but in March Erzerum fell …” (Isaac Don Levine. The resurrected Nations, 1919). Fullerton Leonard Waldo (1877-1933), a journalist from Philadelphia, went to Armenia with inspection purposes. At that time, Armenian republic had only one outlet for receiving outside humanitarian help for thousands orphans and refugees flooding the country in aftermath of genocide perpetrated by Turks. It was Georgia, testified American journalist, a Christian country which profited generously at the expense of its Armenian brethren. “The Georgian customs authorities, I am told, get sixty to seventy per cent of what is confiscated.” (Twilight in Armenia, 1920). It happened hundred years ago and it happened again just recently! For a person unfamiliar with history of these two neighboring peoples, instances of such behavior by Georgian ruling elite may seem to be irrational and even damaging for the country in a long run, but nobody yet abolished the primitive feelings such a toxic mix of arrogance and jealousy capable influence decision-making. “At Tiflis, out of population of one hundred thousand souls, the Georgians are estimated at 22 per cent; and the Armenians at 37 per cent. In the town itself the Georgians are in minority, for they are essentially rural people and unskilled in commerce … Almost all the nobility of the country is Georgian, and very proud of its blood; for that matter, every Georgian call himself noble, and even in the lowest conditions of life you find some of them bearing the title of prince … In comparison with the Georgian aristocracy, the Armenians form what we should call the middle class: very industrious and sharp-witted, they excel in all kinds of business … In their schools the children show remarkable aptitude for learning … The Armenians boast several families of mark; they have given to Russia some illustrious generals, like Lazaref and Loris melikof.” (Eugene Melchior de Vogue. The Tsar and His People or Social Life in Russia, 1891).

All these observations confirm an old wisdom that history repeats itself. Misfortunes and failures did happen in history of the Armenian nation, defeats and losses caused a great pain and sorrow to Armenian people, they were shamelessly deceived and betrayed, but it also true that unique recuperative energy and creative abilities always brought the nation back to life. Theodore Roosevelt said once: “Thrice happy is nation that has glorious history. Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those who neither enjoy much nor suffer much because they live in the grey twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.”

*********************************

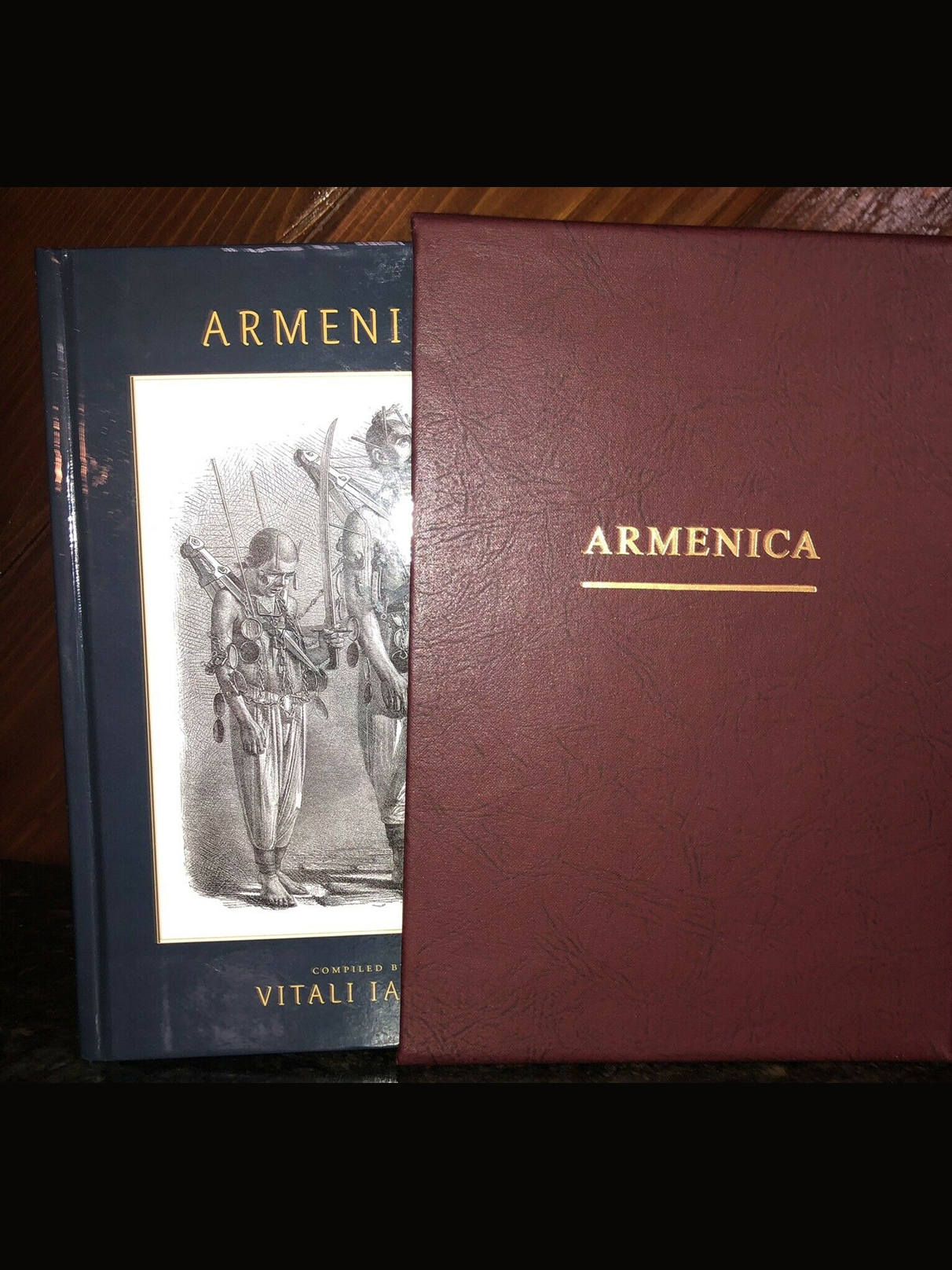

All the excerpts are from the author’s new book, ARMENICA: An Annotated Bibliography or a List of Books on Armenia and Armenians Published in Western Languages up to 2015 and Omitted in Main Bibliographies, (1920). The book has 752 pages, almost 90 color and b/w illustrations, and printed as a luxury edition of only 50 copies in a special protective slipcase.